A Timeline of the Historical Events depicted in Here Lies Love

The Rise and Fall of the Marcos Regime

Early Life of Imelda Romualdez

Imelda Romualdez was born on July 2, 1929 in Manila. Although Imelda came from the wealthy Romualdez clan, her family was considered the poorest members. Her father, Vicente Orestes Romualdez, was a failing law practitioner and windower with five children. After his first wife died, Vicente Orestes married Remedios Trinidad, Imelda’s mother. Together, they had six children, Imelda being the oldest, but they did not have a happy marriage. The children from the first marriage resented their father for not consulting them about Imelda’s mother which forced Remedios and her children to live in the garage to avoid further conflict. At the age of eight, Imelda lost her mother to pneumonia and her family moved back to Tacloban.

In 1949, Imelda won a local beauty contest in Leyte, earning her the title of “Rose of Tacloban.” In 1952, Imelda left Tacloban to live with her cousin. Imelda placed her energy into pursuing acclaim. Her beauty and charm caught the attention of many influential people in Manila's business and political circles, including the mayor, who named her the “Muse of Manila” in 1953, raising her status as a prominent socialite and beauty queen.

When she became the First Lady of the Philippines, Imelda aimed to erase her past and replace it with the narrative that she was born to be the First Lady of the Philippines. She sent bulldozers to destroy the garage where her family once lived and built an “ancestral home” to replace it.

Early Life of Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr.

Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. was born November 27, 1932, in Concepcion, Tarlac. At age 17, he left college early to begin his career as the youngest correspondent in the Korean War. In 1955, Aquino, at 22 years old, became the youngest mayor of Concepción, and in 1959 he became the youngest vice-governor in Tarlac. He quickly progressed in his political career, becoming the governor of Tarlac province in 1961, Philippine senator in 1967, and national leader of the Liberal Party in 1968. He grew to become Ferdinand Marcos’ primary political opponent.

Relationship between Imelda and Aquino

In the early 1950s, Aquino became a consort for the Miss Philippines contest because his boss’s wife was in charge of the beauty contest. His involvement in the pageant likely led him to meet Imelda, who was living with his aunt, the wife of Daniel Romauldez, Paz Gueco. The two got close and saw each other often in 1953. He eventually ended his relationship with Imelda, later revealing that she was too tall for him to dance with her. Aquino married Corazon “Cory” Cojuangco the following year.

October 11, 1954

Ninoy Aquino and Cory Cojuangco get married

Early Life of Ferdinand Marcos

Ferdinand Marcos was born on September 11, 1917, in Ilocos Norte. He attended school in Manila and studied law in the late 1930s at the University of the Philippines. His law background proved to be helpful when he was tried for the assassination in 1933 of a political opponent of his politician father. Marcos was found guilty in November 1939; however, he argued his case on appeal to the Philippine Supreme Court and was acquitted the next year. He then became a trial lawyer in Manila.

During World War II, Marcos was an officer with the Philippine armed forces. During his political campaigns, he claimed to be a leader in the Filipino guerrilla resistance movement and to have received at least 30 awards, medals, and citations from the war. U.S. government archives later revealed that he actually played little or no part in anti-Japanese activities during the war.

After the war, Marcos began his political career. He was a member of the House of Representatives from 1949 to 1959, and of the Senate from 1959 to 1965. While a senator, he served as Senate president from 1963 to 1965. In 1965, Marcos, who was a prominent member of the Liberal Party, left the party after failing to get their nomination for president.

Imelda and Ferdinand’S Marriage

Imelda and Ferdinand Marcos met one evening after a day on the floor of the House of Representatives. Imelda had come to pick up her cousin. 11 days later, on April 17, 1954, the pair were legally married. On May 1, 1954, the ceremony was held and Marcos married Imelda with a ring encircled by 11 diamonds.

Marcoses’ Rise to Power

The shy country girl reportedly had difficulty adjusting to public life; Imelda suffered a nervous breakdown and checked into a New York psychiatric hospital, where she spent a year in therapy. But by 1965, she had shed her inhibitions and campaigned tirelessly for her husband's upset presidential victory.

Imelda returned from New York convinced that a distinctive identity was the key to success, and that art and culture were its vital components. She thought a cultural center would be the ideal vehicle through which to cultivate this among her people. As First Lady, Imelda displayed what some Filipinos called an “edifice complex,” raising corporate funds for construction that critics found ludicrous alongside acres of slum housing. Nonetheless, Ferdinand gained popularity in his first term from the people after borrowing funding from abroad to modernize infrastructure.

Cultural Center of the Philippines, Opened 1969Manila Heart Center, Opened 1975Manila Film Center, Opened 1982February 10, 1969

Aquino delivered his speech entitled “A Pantheon for Imelda,” where he criticized the First Lady’s extravagant ₱50-million Cultural Center, which he dubbed “a monument to shame.” Aquino challenged the center’s construction, given the present suffering of the Filipino people. He called Imelda “The Fabulous One.”

December 30, 1969

Marcos began his second term as president.

In 1969, Marcos was reelected for his second term as president, after which the country faced the consequences of the Marcoses’ debt-fueled spending spree and fell into an economic crisis with rapid inflation. As a result, public dissatisfaction and social turmoil began to fester, and opposition to Marcos intensified on multiple fronts.

December 30, 1965

In 1965, Ferdinand Marcos was elected the 10th president of the Philippines after serving as a lawmaker for the previous 15 years. This followed a campaign that highlighted his heroism during World War I, claims that have been disputed by historians.

Marcos’ Affair with Dovie Beams

November 11, 1970

American actress Dovie Beams revealed details about her almost two year with the President . As proof, she released secret tape recordings of their private interactions. As a means of damage control, the Marcos regime released 10 serialized articles characterizing Beams as a prostitute, a lunatic, and a gold digger. Although it is speculated Marcos had affairs with other women while he was with Imelda, the public scandal caused by Beams worked to shatter the mythology of the Marcoses as the perfect pair that their regime had worked hard to manufacture, chipping away at Marcos’ own carefully crafted public persona as a devoted husband and heroic statesman.

Imelda in Power

Described in CIA reports as the “steel butterfly,” Imelda was herself an “Iron Lady” in a butterfly sleeve. Using her beauty, charm and cunning, Imelda was a political power in her own right; she proved to be much more than a dictator's wife. She controlled public and private funds equal to 50% of the total government budget, with little accountability. As Minister of Human Settlements, she possessed the right to seize any urban property without recourse.

Imelda used her power to fund her lavish lifestyle, notoriously going on extravagant shopping sprees and travel abroad. During her tenure as First Lady, she jetted around the world on countless diplomatic visits both with and without her husband. She used her beauty and charm to enchant world leaders.

December 7, 1972

Imelda survived an assassination attempt on national television when an assailant stabbed her with a bolo knife as she was handing out awards for a civic beautification contest.

She later said, “If there’s somebody who’s going to kill me, why do they have to be, why is it to be a bolo that is so ugly? I wish they put some kind of yellow ribbon, or some kind of a nice thing. Why such an ugly instrument?” Imelda’s survival awakened in her a “sense of mission to a Nietzschean extreme.” She kept her arm in an elegant gold-chain sling even when no longer needed, and she claimed to have never recovered the full use of her right hand years after the incident. Some believed that the assassination attempt was staged to win the people’s sympathy, as it was the year martial law was declared.

During the later years of his presidency, Marcos suffered from lupus erythematosus. As his health deteriorated, Imelda intensified her political presence in order to compensate for his decreased public appearances and detract from questions about her husband’s ailment. In the event of Marcos’ possible passing, there was speculation that she expected to succeed him as president even though she was disliked by Marcos’ military officers.

First Quarter Storm

January to March 1970

Thousands of Filipinos, led by students, protested for political reform, including a restructuring of the U.S.-based constitution, the ending of American imperialism, and embracing more socialist ideologies. The demonstrations culminated in the bombing of Plaza Miranda on August 21, 1971, which killed ninepeople and injured others. Marcos placed blame on the Communist Party.

MARTIAL LAW

September 21, 1972

After signing it into action on September 21, 1972, Marcos publicly declared martial law on September 23 through Proclamation 1081, placing the country under autocratic rule as he dissolved Congress and seized control of the courts. Marcos proclaimed martial law to save the Philippines from communism, he said, but instead it was a means for the Marcoses to stay in power at the expense of the suffering of the Filipino people. During the nine years that martial law lasted, 70,000 people were incarcerated; 35,000 were tortured; and 3,200 were killed.

70,000 incarcerated. 35,000 tortured. 3,200 killed.

AQUINO’S Imprisonment, Exile, AND ASSASSINATION

September 22, 1972

Along with other members of the opposition, Aquino was arrested prior to the public declaration of martial law. He spent seven years in prison.

March 1980

Imelda visited Aquino in the Philippine Heart Center, one of her edifices, where he had been taken for examination after a heart attack. She informed him that Marcos would release him to go to the United States for a heart operation. Aquino stayed there for three years.

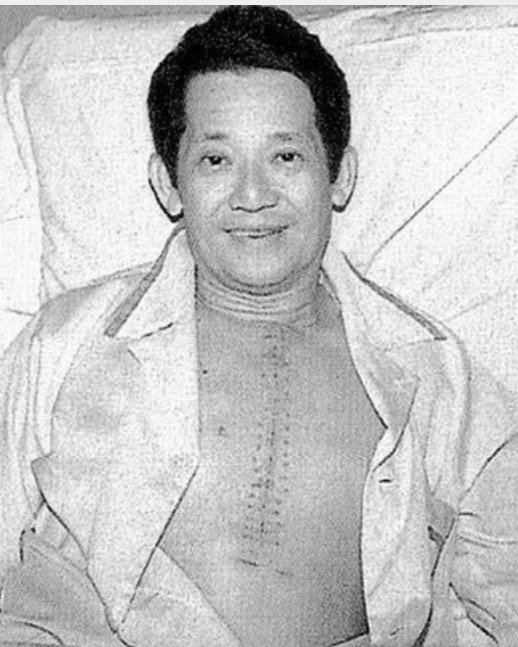

Ninoy After his successful triple heart bypass operation in the u.s. Receiving medical check-ups in the Heart CenterJanuary 17, 1981

Martial law is lifted to satisfy American policymakers; however, the Marcos family retains most of the apparatus of martial law, allowing them to maintain their power.

June 16, 1981

Another presidential election was held. With much of the opposition boycotting, Marcos won by a huge margin

May 1983

After hearing reports about Marcos’ sickness, Aquino decided it was time for him to return to the Philippines and make his bid for the presidency. Imelda offered Aquino a bribe to stay in Boston and warned him that the Marcoses would not be able to protect him if he returned.

ninoy being escorted by the military off his flightNinoy Saying his prayers prior to landingAugust 21, 1983

Ninoy Aquino was assassinated on the tarmac of Manila International Airport, now called Ninoy Aquino International Airport, upon his return from exile in the United States. Aquino’s assassination sparked further outrage among Filipinos toward the Marcos regime.

It is not known for certain who ordered Aquino’s assassination. However, the CIA speculated that Imelda conspired with General Fabian Ver, chief of staff of the Philippine Armed Forces at the time, to kill him.

September 1, 1983

Ninoy Aquino’s funeral brought thousands of Filipinos to the streets of Manila. During the funeral procession, Imelda Marcos held a dinner at the palace for U.S. senator Mark Hatfield, who reportedly was on a private visit.

Crowds gathering in Luneta Park to see Ninoy's coffinCoffin moving through crowds in funeral processionPEOPLE POWER

REVOLUTION

February 7, 1986

As the people’s dissatisfaction with the regime grew, Marcos held a snap election, in which Corazon “Cory” Aquino, Ninoy’s widow, ran for president. Marcos’ opposition came together to challenge him and rally for Cory. Despite claims of fraud from both observers in the Philippines and the United States, Marcos was declared the winner of the election. Those who opposed Marcos called for protests and civil disobedience, but were warned that they could be arrested for seditious behavior.

February 22, 1986 – February 25, 1986: People Power Revolution

The People Power Revolution. On February 22, 1986, hundreds of Filipinos gathered at Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) in Manila to participate in a peaceful mass demonstration. People flooded the streets to protect military defectors who joined their cause, serving as barriers to tanks and armed battalions that Marcos sent in retaliation. The revolution was nonviolent and ended without a single casualty.

February 25, 1986

The Marcoses fled on a U.S. marine helicopter to Hawaii, where they remained in exile until 1991.

Today, 37 years after the Marcoses were exiled from the Philippines, Imelda’s son Ferdinand “Bong Bong” Marcos Jr. is president of the Philippines

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Afinidad-Bernardo, Deni Rose M. “Edifice Complex: 31 Years of Amnesia.” Philstar. Philstar.com . Accessed April 30, 2023. https://newslab.philstar.com/31-years-of-amnesia/building-spree.

Bonner, Raymond. Waltzing with a Dictator: The Marcoses and the Making of American Policy. New York: Vintage Books, 1988.

Camille Mendoza, Carla. “The Miserable Mrs Marcos.” The Miserable Mrs Marcos | Asia Literary Review. Asia Literary Review. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.asialiteraryreview.com/miserable-mrs-marcos.

Campbell, Colin. “A Million Filipinos Line the Aquino Funeral Route.” New York Times, September 1, 1983. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1983/09/01/137463.html?pageNumber=4.

Chapman, William. “Hundreds of Thousands March through Manila to Honor Aquino.” The Washington Post. WP Company, September 1, 1983. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1983/09/01/hundreds-of-thousands-march-through-manila-to-honor-aquino/7a728838-cf5b-4de9-81a6-b70f8d805a15/.

Hau, Caroline S. “Dovie Beams and Philippine Politics: A President’s Scandalous Affair and First Lady Power on the Eve of Martial Law.” Philippine Studies: Historical & Ethnographic Viewpoints 67, no. 3/4 (2019): 595–634. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48564573.

Joaquin, Nick. The Aquinos of Tarlac: An Essay on History as Three Generations. Manila: Solar Pub. Co., 1986.

Komisar, Lucy. Corazon Aquino: The Story of a Revolution. Metro Manila: National Book Store, 1988.

Kurtz, Howard. “Fall of the Steel Butterfly.” The Washington Post. WP Company, April 17, 1990. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1990/04/17/fall-of-the-steel-butterfly/c554555f-1ba5-4dda-b2f8-b6c2d4c41dbc/.

Lacaba, Jose F. “The First Quarter Storm Was No Dinner Party, Part 1.” Positively Filipino | Online Magazine for Filipinos in the Diaspora. Positively Filipino | Online Magazine for Filipinos in the Diaspora, January 20, 2014. http://www.positivelyfilipino.com/magazine/the-first-quarter-storm-was-no-dinner-party-part-1.

Maglipon, Jo-Ann Q. “Martial Law Stories: Remembering.” Positively Filipino | Online Magazine for Filipinos in the Diaspora. Positively Filipino | Online Magazine for Filipinos in the Diaspora, April 24, 2019. http://www.positivelyfilipino.com/magazine/martial-law-stories-remembering.

Mydans, Seth. “Marcos Flees and Is Taken to Guam; U.S. Recognizes Aquino as President.” New York Times, February 26, 1986. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/02/26/world/marcos-flees-and-is-taken-to-guam-us-recognizes-aquino-as-president.html.

Overholt, William H. “The Rise and Fall of Ferdinand Marcos.” Asian Survey 26, no. 11 (1986): 1137–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/2644313.

Pobre, Addie. “Look Back: The 1972 Assassination Attempt on Imelda Marcos.” RAPPLER. Rappler, December 7, 2016. https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/154707-look-back-assassination-attempt-imelda-marcos/.

Sison, George. “How Imelda Confirmed Ferdinand Marcos' Affair with Dovie Beams.” Lifestyle.INQ. Lifestyle.INQ, March 4, 2017. https://lifestyle.inquirer.net/256104/imelda-confirmed-ferdinand-marcos-affair-dovie-beams/.